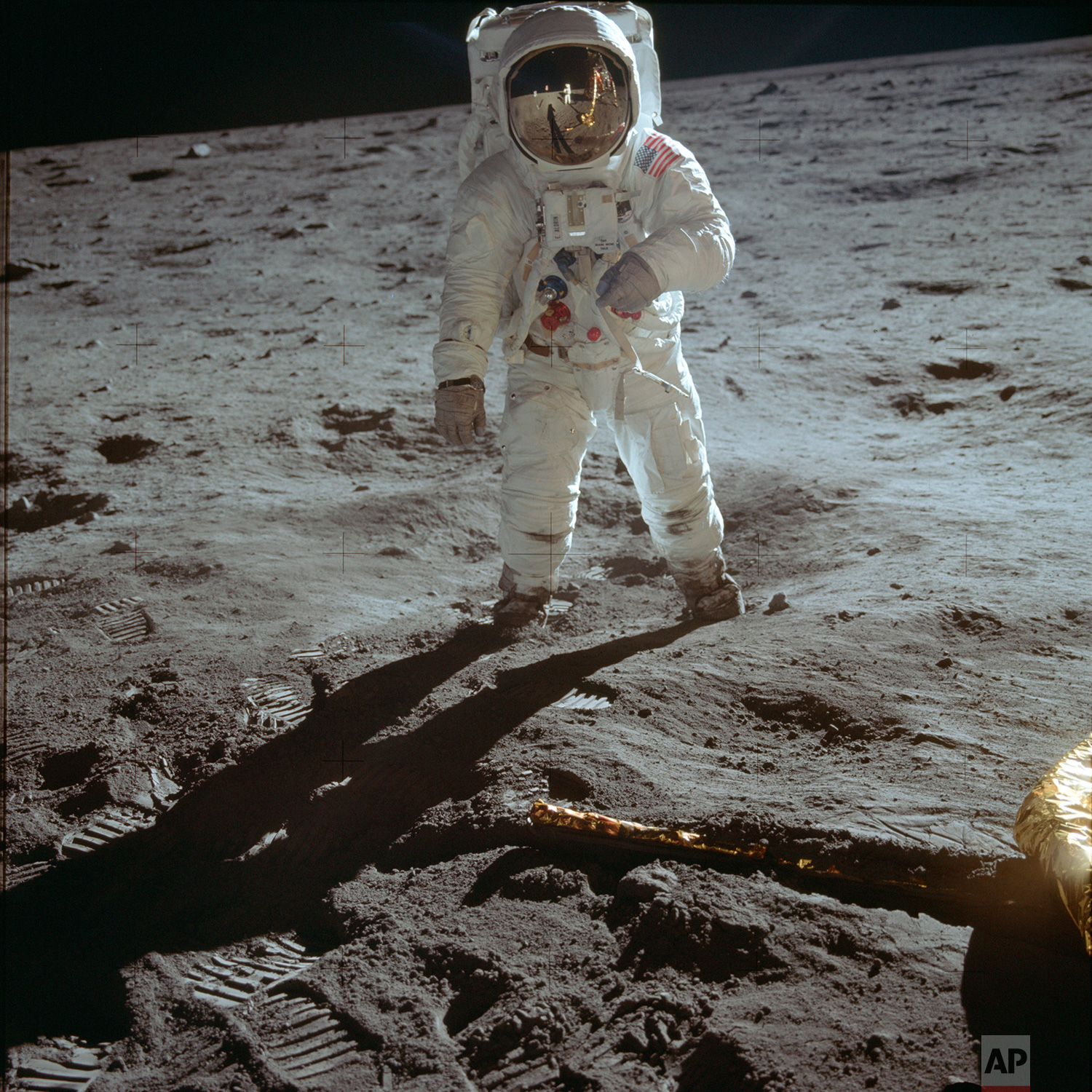

Two Americans landed on the moon and explored its surface for some two hours Sunday, planting the first human footprints in its dusty soil. They raised their nation's flag and talked to their President on earth 240,000 miles away.

Both civilian Neil Alden Armstrong and Air Force Col. Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin Jr. reported they were back in their spacecraft at 1:11 a.m. EDT Monday. "The hatch is closed and locked," Armstrong reported.

Millions on their home planet watched on television as the pair saluted their flag and scoured the rocky, rugged surface.

The first to step on the moon was Armstrong, 38, of Wapakoneta, Ohio. His foot touched the surface at 10:56 p.m. EDT and he remained out for two hours and 14 minutes.

His first words standing on the moon were, "That's one small step for man, a giant leap for mankind."

Twenty minutes after he stepped down, Aldrin followed. "Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful," he said. "A magnificent desolation."

He remained out for one hour and 44 minutes.

Their spacecraft Eagle landed on the moon at 4:18 p.m., and they were out of it and on the surface some six hours later.

At the end, mission control granted them extra time on the lunar surface. Armstrong was given 15 extra minutes, Aldrin 12.

Even while they were on the surface, the seismometer they installed to study the moon's interior was picking up the shudders created by Aldrin as he hammered tubes into the lunar crust to take soil samples.

Earlier, mission control reported that a laser beam shot from earth to the moon had been reflected back by a small mirror set on the surface by the astronauts. But scientists at Lick Observatory in California later said the initial test had failed because the beam was 50 miles off target.

There were humorous moments in the awkward climbing out and in the spacecraft. When Aldrin backed out of the hatch, he said he was "making sure not to lock it on the way out."

Armstrong, on the surface, laughed. "A pretty good thought," he said.

Once back in the spaceship they began immediately to repressurize the cabin with oxygen. They stowed the samples of rocks and soil.

"We've got about 20 pounds of carefully selected, if not documented samples," Armstrong said, referring to the contents of one of two boxes filled with lunar material.

The minutes behind were unforgettable for them, and for the world.

The moments ahead were still full of hazard. Monday, at 1:55 p.m., they are scheduled to blast off from the moon to catch up with their orbiting mothership above for the trip home.

President Nixon's voice came to the ears of the astronauts on the moon from the Oval Room at the White House.

"This has to be the most historic telephone call ever made," he said. "I just can't tell you how proud I am... Because of what you have done the heavens have become part of man's world. As you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquillity, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to man.

"All the people on earth are surely one in their pride of what you have done, and one in their prayers that you will return safely..."

Aldrin replied, "Thank you Mr. President. It is a privilege to represent the people of all peaceable nations." Armstrong added his thanks.

Armstrong's steps were cautious at first. He almost shuffled.

"The surface is fine and powdered, like powdered charcoal to the soles of the foot," he said. "I can see my footprints of my boots in the fine sandy particles." Armstrong read from the plaque on the side of Eagle, the spacecraft that had brought them to the surface. In a steady voice, he said, "Here man first set foot on the moon, July, 1969. We came in peace for all mankind." As in the moments he walked alone, Armstrong's voice was all that was heard from the lunar surface.

He appeared phosphorescent in the blinding sunlight. He walked carefully at first in the gravity of the moon, only one-sixth as strong as on earth. Then he tried wide gazelle-like leaps.

Aldrin tried a kind of kangaroo-hop, but found it unsatisfactory. "The so-called kangaroo-hop doesn't seem to work as well as the more conventional pace," he said. "It would get rather tiring after several hundred."

In the lesser gravity of the moon, each of the men, 165 pounders on Earth, weighed something over 25 pounds on the moon.

Armstrong began the rock picking on the lunar surface. Aldrin joined him using a small scoop to put lunar soil in a plastic bag.

Above them, invisible and nearly ignored, was Air Force Lt. Col. Michael Collins, 38, keeping his lonely patrol around the moon for the moment when his companions blast-off and return to him for the trip back home. Collins said he saw a small white object on the moon, but didn't think it was the spacecraft. It was in the wrong place.

Back in Houston, where the nearly half-moon rode the sky in its zenith, Mrs. Jan Armstrong watched her husband on television. "I can't believe it is really happening," she said.

Armstrong surveyed the rocky, rugged scene around him. "It has a stark beauty all its own," he said. "It's different. But it's very pretty out here."

They took pictures of each other, and Aldrin shot views of the spacecraft against the lunar background.

In a world where temperatures vary some 500 degrees, from 243 degrees above zero in sunlight, to 279 below in shadow, the men in the spacesuits felt comfortable.

Aldrin reported, "In general, time spent in the shadow doesn't seem to have any thermal effects inside the suit. There is a tendency to feel cooler in the shadow than out of the sun."

And here's how the historic walk was documented here in Canada by the Globe and Mail.

Globe and Mail

with files from Newstalk 1010